Part 1: Extra-terrestrial and indigenous peoples

All languages that are not natural languages – in other words, they have not developed historically and are spoken (or expressed in gestures) by people – are known in linguistics as artificial languages or constructed languages. This includes planned languages such as Esperanto, fictional languages such as Klingon from Star Trek or Quenya from The Lord of the Rings, and formal languages such as SQL, HTML or LaTeX. Even slang or pretend languages created by children, for example, French Verlan, belong in a very general sense to constructed languages, and so do special languages and secret languages. The English word ConLanguages (which comes from “constructed languages”; for linguists, this is a typical example of a portmanteau word) is also used internationally to refer to all constructed languages.

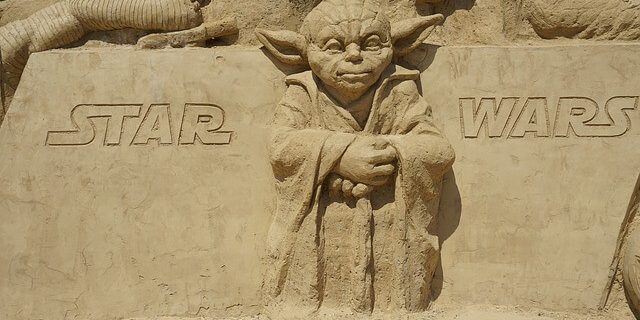

I would like to introduce you to the various types of artificial languages in a short series of articles. Today we will start with fictional languages: These form an important part of fictional worlds and we come across them in fantasy and science fiction books and films. The most well-known examples come from Star Trek, Star Wars and of course The Lord of the Rings. In a remarkable number of cases, we also see elements coming from the indigenous languages of America.

The author of The Lord of the Rings J.R.R. Tolkien was a philologist and even as a child he was trying to invent his own languages. For the people of Middle Earth, he created a multitude of languages for the dwarves, Orcs, humans, and Elves. The Elven languages make up a whole family of languages in which Tolkien applied the scientific rules of historical sound changes. The High-Elven language Quenya is based on Latin grammar and Finnish and Greek phonetics. Sindarin, on the other hand, combines elements from the phonetics and grammar of both Welsh and old-German. In the meantime, fans of these languages have devised extensive language descriptions that are partly based on Tolkien’s own records and partly on texts coming from the Lord of the Rings.

Klingon was the first language to be developed specifically for an extra-terrestrial life form in science fiction films. Up to that point, such languages had been mainly depicted with pointless gibberish or using sounds such as beeping or twittering. However, in 1984 the linguist Marc Okrand from Paramount films was tasked with developing an entire language for the Klingons in Star Trek. Okrand was an expert in the indigenous languages of America and, for this reason, key elements of the phonetics originate from Tlingit, which is spoke in South East Alaska and on the Pacific Coast of Canada. Okrand took the characteristic sound –thl- [tɬ] from the Mexican language Nahuatl.

In addition, linguists discovered phonetic elements of Hindi, Arabic, and Yiddish. To emphasize the exotic nature of the language, Okrand chose the exceptionally rare sentence order Object-Predicate-Subject, which is described, for example, for Hixkaryana, a Carib language from the Amazon. The fascination shown by “trekkies” for this language has resulted not only in extensive dictionaries and grammar books about Klingon, but there is also a Hamlet translation and a Klingon Language Institute with more than 2,500 members who regularly speak this language.

The first Star Wars films used only slightly modified natural languages for the extraterrestrial species: Master Yoda speaks using the word order Object-Subject-Verb which is also very rare and occurs, for example, in the indigenous language Xavante in Brazil. Jabba the Hutt produces noises that are based on the Quechua language. Meanwhile, for larger film productions it is practically taken for granted that linguists will develop the artificial languages. Examples include Na’vi from Avatar, which was devised by Paul Frommer, or Dothraki and Valyrian from Game of Thrones, created by David J. Peterson. These languages boast an extensive vocabulary and clearly defined grammar. Fans create dictionaries, wikis, and blogs; they write literary texts and arrange meet-ups where the language is taught and spoken. Yet they also transfer their own separate culture, even if it is fictional. The linguist Arika Okrent actually criticized the translation of the Vulcan greeting “Live long and prosper” into the Klingon yIn nI’ je chep when she said, “This is something that a Klingon would never say”.

Adiaŭ kaj vidi vin baldaŭ: In the second part of this series, we will take a look at planned languages.